School Travel Planning (STP), a community-based approach to increase rates of active travel to school, was brought to Toronto in the mid-1990s to address such concerns. Since then, Green Communities Canada (GCC) has been a major contributor to the growth of STP in Canada, piloting the model across four Canadian provinces between 2006 and 2009. By 2012, GCC worked alongside multiple partners to successfully introduce the program to over 120 schools across the country.

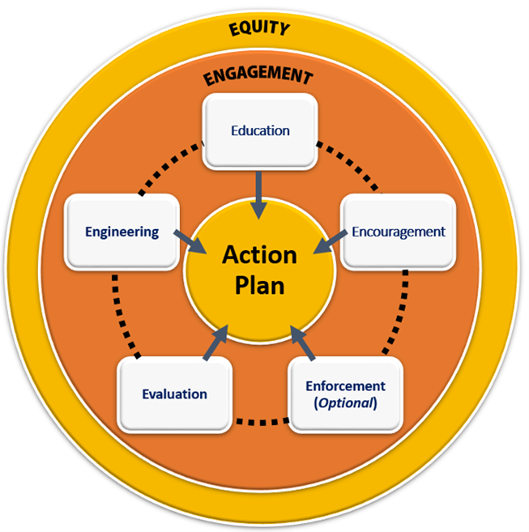

GCC’s STP program, inspired by the UK’s Safe Routes to School initiative, uses the “Five E’s” framework – education, encouragement, engineering, enforcement, and evaluation – to increase active travel to and from school.

Figure 1. GCC’s “Five E’s” framework for School Travel Planning.

Reviewing Our STP Framework

In recent years, however, increasing instances of violence against Black individuals and communities have led many groups to re-evaluate their “Five E’s” framework . In particular, US-based non-profit, Safe Routes Partnership (SRP) reviewed their SRP Framework and made the decision to remove enforcement and add engagement.

“The actions of our American counterparts prompted staff at GCC to review how our current STP framework was failing to address issues of equity and oppression,” states Laura Zeglen, former School Travel Planner with GCC. “Our team felt it was our responsibility to reflect on prejudices that may have existed within the framework [therefore], we set to work to explore how the framework could be improved to be more inclusive and equitable.”

To begin the review of our STP framework, GCC created an Equity Working Group. Together, the Equity Working Group established two primary questions to consider:

- Should GCC remove enforcement from the “Five E’s” of our STP Framework?

- How can GCC adapt our STP framework to bolster anti-oppression and advance equity?

Methods

The Equity Working Group reviewed reports, academic journal articles, essays, news articles, organizational statements and policies, blog posts, webinars, and resources for practitioners. The group also held interviews with critical community informants on topics of police in schools, anti-oppression, and equitable engagement.

Findings

The review and discussions culminated in several key findings related to enforcement, equity, and engagement. These key findings, along with the answers to the above two questions, are addressed in full in our recently published report, “Equity and Engagement in School Travel Planning: Reviewing Our “Five E’s” Framework” and are summarized below.

Use of Traditional Enforcement

From the research conducted, we established three main themes under the category of enforcement.

Theme 1: Effectiveness of Traffic Enforcement

Research concluded that the likelihood of speeding or fatal vehicular crashes were reduced when police was present to enforce traffic laws. However, dangerous driving behaviour returned to previous levels in the absence of police.

For these reasons, traditional methods of police enforcement are not effective at sustaining safer neighbourhoods and streets. Moreover, traditional police enforcement is linked with racial biases and instances of individuals being killed or harmed during routine traffic stops.

Theme 2: Police Presence in School Zones

The presence of police in schools is a strongly contested subject, with some individuals stating that it helps them feel safer, whereas some, particularly from underrepresented communities, state that it makes them feel unsafe.

For example, one survey of traditionally underrepresented youth found that 15 per cent of individuals felt unsafe in the presence of police. Police presence in schools is a highly contested topic, therefore, we concluded that the STP process should prioritize consultations with individuals prior to the decision to implement police-based enforcement measures in communities.

More specifically, it is important to consult with students who are often underrepresented, as this is an integral step in practicing anti-oppression and advancing equity.

“In today’s era of police reform, it’s becoming more and more evident that we should never make assumptions that police enforcement is equally beneficial to every community we work with, because for some, it can do more harm than good,” reflects Charlotte Estey, School Travel Planner with GCC.

Theme 3: Alternatives to Traditional Enforcement

The racial bias and lack of efficacy of police enforcement leads to the need for an alternative means of dangerous driving prevention. Instead, Automated Speed Enforcement (ASE) can be used as an effective tool for reducing dangerous driving behaviour without the consequence of racial biases.

Further, the design of our built environment can have a significant impact on individuals’ choices to pursue active modes of travel. As a result, using punitive enforcement to discourage unwanted travel behaviours may not solve the underlying issue. Rather than turn to enforcement, the STP framework should prioritize engineering measures to address design issues through an equity and engagement-based lens.

Finally, when enforcement is pursued, alternatives to traditional punitive measures should be considered, perhaps taking inspiration from Restorative Justice and Transformative Justice frameworks.

Figure 2. Two community parents discuss concerns around the school’s active travel infrastructure.

How to Practice Engagement

In addition to enforcement, we conducted research to determine best practices for improving community engagement during the STP process.

Theme 1: Build Relationships

Our research established that relationship building early in the STP process is essential to authentic and meaningful community engagement. The relationship building process is an intentional and time-intensive process that prioritizes members’ perspectives and requires flexibility to accommodate the needs of the community.

Overall, community engagement should be pursued using non-extractive approaches, and must be done actively throughout the duration of the entire STP process (2-3 years).

Theme 2: Reduce Barriers to Participation

Differences in race, class, ability, and age can impact how certain AST decisions affect an individual; while it can benefit one group, it may act as a disservice to another. For this reason, during the STP process, it is critical to create a safe and inclusive space to discuss the experiences and barriers of historically marginalized groups.

Further, when making STP decisions, practitioners should emphasize consensus-based decision making, as opposed to majority voting. Barriers to participation can also be reduced by providing participants with incentives and support (e.g., honorariums, bus tickets, childcare, etc.) for their involvement.

Theme 3: Address Transportation Inequities

Throughout history, municipal and transportation plans have neglected the needs of marginalized communities. This has resulted in neighbourhoods with poor access to public transportation, little to no traffic calming strategies, and inadequate active transportation infrastructure.

In addition, infrastructure improvements can often lead to gentrification of certain areas. For this reason, individuals in marginalized communities may view the STP process with skepticism or distrust. It is important to understand this complex history, and to respect an individual’s decisions, even if it opposes the STP goals.

Theme 4: Support Participation of Children and Youth

Although the STP process impacts youth most directly, they are often not involved or are under-represented in the overall process. Involving youth in the process, through creating data collection surveys, or designing neighbourhood infrastructure, will allow them to offer their perspectives and creativity to benefit the community. For more detailed tips on how to support youth engagement, read the Voice Opportunity Power and the Active School Travel Toolkit, created by the Town of Ajax.

“Involving students’ voices and opinions in the School Travel Planning process is an integral step in building equitable engagement. Often, School Travel Planning is led by a committee of school staff, government employees, and parents, with little to no consultation with school youth,.” states Isooda Niroomand, former School Travel Planner with GCC. “Youth voices must be prioritized and represented to work towards more inclusive, and oftentimes, more creative solutions as well.”

Figure 3. Group of students at St. Margaret school contributing to a discussion about active modes of travel to school.

Our Revised Framework

After reviewing the research and conducting interviews with informants, GCC was able to draw conclusions about the two guiding questions.

Should GCC remove enforcement from the “Five E’s” of our STP framework?

As outlined earlier, traditional police enforcement inadvertently targets historically marginalized communities, and does not result in sustained improvements in road safety upon their absence. For this reason, GCC has decided to modify enforcement to become an optional “E” within our STP framework.

Before enforcement is implemented, intensive community consultation must be conducted, and collective community agreement must be reached. Additionally, when enforcement is added, GCC recommends considering Transformative and Restorative Justice as alternatives to traditional punitive enforcement.

How can we adapt our STP framework to be anti-oppressive and be more equitable?

GCC’s Equity Working Group unanimously agreed that ongoing and in-depth relationship building is integral to achieving equitable outcomes from the STP process. For this reason, equity and engagement were added as two additional E’s to the “Five E’s” framework, effectively modifying it to become the “Seven E’s” framework.

In the new model, engagement overarches the original “Five E’s”, demonstrating the need to prioritize community engagement at every step of the STP process. Equity was added as the final “E” of the framework (see Figure 4), indicating the need for practitioners to establish fair, equal, and just access to active school travel benefits for every individual and group involved.

Figure 4. GCC’s revised STP framework, now referred to as the “Seven E’s”.

“This framework is a significant step forward in incorporating our organization’s equity, diversity, and inclusion strategy into our programming work. I hope that it will encourage practitioners across the country to approach their work with justice at the forefront, and that this will tangibly improve equitable engagement and school travel conditions for many children and their families,” states Brianna Salmon, Executive Director of GCC.

Overall, the report “Equity and Engagement in School Travel Planning: Reviewing Our “Five E’s” Framework” is not intended to be prescriptive, but to be used as a tool to guide practitioners in their STP work moving forward. We encourage you to read the entire report and download the accompanying checklist to create more impactful School Travel Planning initiatives with engagement and equity at the forefront.

Written with significant contributions from Sabat Ismail.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks