Road closure barriers placed at Tyneburn Crescent on Havenwood Drive (photo by: Green Communities Canada).

School Streets are an innovative solution to encourage active school travel, improve air quality, and increase road safety for children, caregivers, and educators. To test and apply School Streets on a larger scale, Green Communities Canada (GCC) and 8 80 Cities formed a partnership to lead the Ontario School Streets Pilot (OSSP). The project included the planning and piloting of School Streets in Markham, Mississauga, and Hamilton, with Kingston joining the project later on.

The pilots were successfully implemented in spring 2022 in all four communities, with interesting successes and lessons learned from each project site. Our partners at 8 80 Cities have worked hard over the summer months to compile the pilot data and make key recommendations for future School Streets projects.

This information can be found in the newly released Ontario School Streets Pilot Program Summary Report.

Continue reading this blog for a high-level summary of the projects, key findings, and recommendations. We encourage you to read the full Summary Report for more details!

Project

The OSSP project began in September 2021 and was completed in June 2022. The project was coordinated by 8 80 Cities, who provided technical assistance, facilitated peer-to-peer coaching and knowledge exchange, and general project guidance.

The key goals of the project were to:

- Increase active school travel

- Spark conversations about Vision Zero and road safety

- Continue the momentum of School Streets

- Reduce traffic congestion around schools

- Provide a safe and fun place for children to start and end their day

- Encourage municipalities to provide more funding

The project proceeded in three key phases, with Phase 1 (May 2021 – May 2022) focusing on planning, Phase 2 (May – June 2022) was implementation and monitoring, and finally, Phase 3 (June – September 2022) was to facilitate evaluation and knowledge sharing.

Pilot Sites

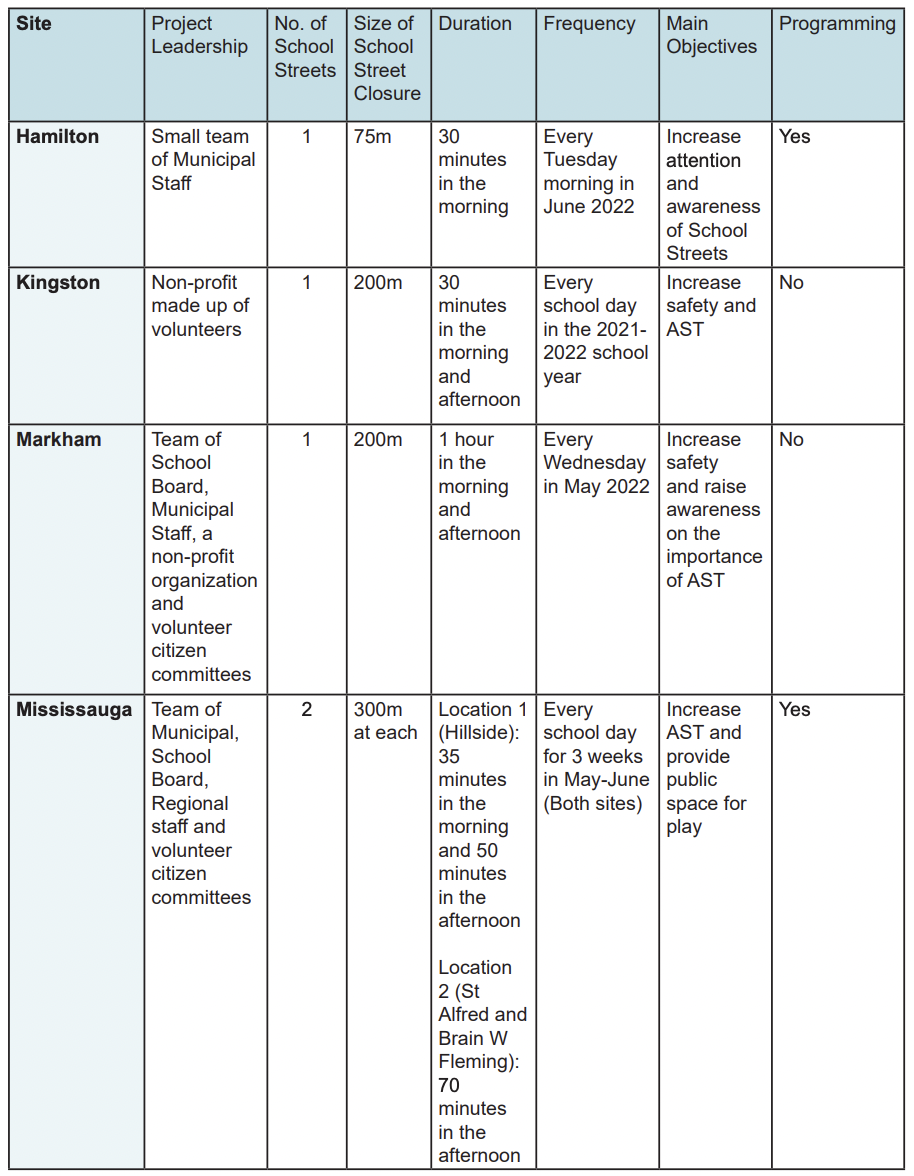

The OSSP pilot sites included Hamilton, Kingston, Markham, and Mississauga, all of which ranged in scale, duration, and objectives. Refer to the overview table for a high-level comparison of pilot sites.

Overview of School Streets Table

Hamilton

Planning

The Hamilton pilot had five main objectives, including the goal to increase active travel and reduce car travel during the pilot, create more accessible public space for active transportation and play, connect the pilot to other initiatives at schools and the City of Hamilton, increase awareness of School Streets, and make the pilot scalable and adaptable to other schools.

The school street took place at Strathcona Elementary School on a portion of Lamoreaux Street. This school was selected based on community readiness and capacity, equity with consideration for Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board’s (HWDSB) Equal Opportunities Initiative, mode share with a low percentage of students receiving bus service, and additional characteristics of the school and neighbourhood.

The City of Hamilton led community engagement in the form of key stakeholder meetings, pop-up engagements, focus groups, public meetings and open houses, and online/print surveys.

Implementation

Lamoreaux Street was closed to vehicles every Tuesday morning in June from 8:30 – 9:00 am. To create the school street, the City of Hamilton used a combination of traffic pylons, road closed signs, volunteers, and as an additional precaution, utilized service vehicles at each closure location. Accordingly, no vehicles were permitted to enter the space, making this a “hard” closure.

Programming

On the first day of the school street, families came with hula hoops, skipping ropes, and games to use on the car-free street. The team encouraged the school community to play before the school day and coordinated programming around air quality in partnership with Green Venture.

Families playing in the school street on Lamoreux St. (photo by: City of Hamilton)

Results

The School Streets project resulted in a 7% increase in active travel to school (5% increase in walking, 1% increase in biking, 1% increase in wheeling), and a 9% decrease in vehicle use.

Prior to the implementation of the school street, many parents in the community had expressed an interest in closing down Lamoreaux Street before and after school. As a result, the response to this school street was overwhelmingly positive.

“We’d definitely like to see this repeated as much as we could in the future. Perhaps it could be seasonal for spring and summer.” – Julia Lillicrop, a parent, and president of the Home & School Association for Strathcona Elementary School

The community embraced the initiative, suggesting the possibility of implementing longer term School Streets in Hamilton in the future.

Markham

Planning

The School Streets pilot in Markham had six main objectives; including the goal to be inclusive and accessible to all users, improve community safety, educate community members about the benefits of active transportation, prioritize sustainability, and generate a fun space for the entire community.

The school street was launched at John McCrae Public School on a portion of Stricker Avenue, allowing a 200 metre school street zone. The school was chosen because it already carried a lot of momentum in other active transportation initiatives, such as its participation in the Walking Wednesday program. Further, the school had expressed concerns over hazardous road designs, highlighting the kiss-and-ride area that the school street could help address.

This School Streets project, created by the Markham Team of York Regional District School Board (YRDSB) and the City of Markham staff, aimed to improve community engagement through stakeholder meetings, public meetings, and online and print surveys.

Implementation

Every Wednesday in May, Strickler Avenue was closed for an hour each morning (between 8:15-9:15 am) and afternoon (between 3-4 pm). To close the street, the city implemented lightweight barricades, ‘road closed’ signs, orange pylons, and the York Region Police parked their cars at the school street entrances. Some vehicles were permitted entry, including residents who live on Strickler Avenue, school staff, and school buses. Although these groups were permitted entry, they were required to drive at a walking pace while being escorted by a volunteer.

Programming

On launch day at John McCrae PS, the school was joined by the school trustee, the mayor of Markham, and city councillors. There was no additional programming or activities on the street after launch day, as the school streets’ intended use was for active travel.

Elected officials, organizers, and community members gathered at John McCrae PS for the launch of the School Streets pilot (Photo: YRDSB)

Results

The School Streets project resulted in a 6% increase in active travel to school (3% increase in walking, 1% increase in walking part way, and 2% increase in wheeling) and a decrease in dangerous driving behaviour. Overall, the school observed a decrease in illegal parking, U-turn instances, speeding in school zones, and observed improved air quality in the school street zone.

After the pilot, 44% of students said that they would like the school street to continue, and 47% were unsure if they would like it to continue. The high percentage of unsure students could have been because they had not used the school street on their way to or from school. Residents of Markham were the most supportive of this initiative, with 60% stating their approval of more School Streets programs in the future.

This School Streets pilot created a strong foundational relationship between the school board and the City of Markham, with both groups expressing their intentions to collaborate on active school projects again in the future.

Mississauga

Planning

The School Streets pilot in Mississauga had four main objectives; to increase active travel, increase investment in active school travel programs, create more accessible public spaces for play, and increase awareness and acceptance of School Streets.

Two separate School Streets pilots were launched in Mississauga. One was held at Hillside Public School on a portion of Kelly Road, allowing a 300 metre school street zone. The other took place in front of St. Alfred Separate School and Brian W. Fleming Public School on a portion of Havenwood Drive, also allowing a 300 metre school street zone.

The two pilot locations were selected based on four main criteria:

- Mode share (low % of students bussing, high % already using active travel);

- Neighbourhood characteristics (not on a public transit route, not a collector or arterial route, not a busy road);

- Readiness, leadership and capacity (support from various stakeholders); and

- Equity (schools who scored higher on socioeconomic vulnerability were prioritized).

Although Hillside PS fit more of the criteria points than St. Alfred and Brian W. Fleming, the other two schools scored much higher on their socioeconomic vulnerability.

The planning of these two School Streets was a collaborative effort between the City of Mississauga, members from the Region of Peel, the school boards, Mississauga’s Traffic Safety Council, and the local student transportation consortium. These groups engaged the public, students, parents, teachers, and local residents using various methods, including small group and large group planning meetings, one-on-one conversations, newsletters, emails, and social media.

Implementation

Every day from May 9-27th, Kelly Road in front of Hillside PS was closed for 35 minutes in the morning (between 8:15-8:50 am) and for 50 minutes in the afternoon (between 2:30-3:20 pm). The street on Havenwood Drive, in front of St. Alfred and Brian W. Fleming was closed to vehicles from May 16th -June 3rd for 50 minutes every afternoon (between 2:30-3:40 pm).

Both streets were closed with lightweight barricades, ‘road closed’ signs, and volunteers located at each end of the closure. Vehicles that were permitted entry (residents, caregivers with accessibility needs, special education school buses) were required to drive at a walking pace while being escorted by a volunteer.

Programming

The School Streets at Hillside PS and at St. Alfred and Brian W. Fleming organized programming that corresponded with weekly themes. These themes included road safety, health and wellness, and the environment. To address concerns of food security, the programming at St. Alfred and Brian W. Fleming also included daily healthy snacks for students to grab as they left school in the afternoon.

Students playing with bubbles in the car-free street (photo by: Green Communities Canada).

Results

The School Streets project resulted in a 6% increase in active travel to school (3% increase in walking, 1% increase in walking part way, and 2% increase in wheeling) and a decrease in dangerous driving behaviour. Overall, the school observed a decrease in illegal parking, U-turn instances, speeding in school zones, and observed improved air quality in the school street zone.

The School Streets project at Hillside PS led to a 20% increase in active travel to school, with the number of students choosing to walk, wheel, or roll to school rising from 49% to 69%. The school recorded a 7% increase in active school travel from pre-pilot levels even two weeks after the pilot. In addition, there were 3.3 times more cyclists on the road, 40% less vehicle traffic in the morning, and 33% less vehicle traffic in the afternoon.

The School Streets project at St. Alfred and Brian W. Fleming led to a 4% increase in active travel to school, with the number of students choosing to walk, wheel, or roll to school rising from 56% to 60%. In addition, there were 2 times more cyclists on the road, and an average of 85 fewer cars on the road.

After the completion of these pilot programs, the three schools were awarded $500 by the Mississauga Traffic Safety Council to promote further active school travel initiatives in their communities. Hillside PS even requested an additional bike rack to accommodate the growing number of students choosing to bike to and from school.

Full bike racks at St. Alfred (photo by: Green Communities Canada).

Overall, the awareness and acceptance of School Streets increased in all three communities. Prior to the pilot implementation, 78% of community members refused the idea of establishing a school street. After the pilot, this number dropped by 40%, down to 38%. Further, there was a 19% increase in awareness of the positive impact that School Streets have for communities. These projects also gained significant media coverage, with over 650,000 reads on news article highlights, and reached over 250,000 individuals on Twitter and Facebook.

The biggest challenge of the School Streets pilots at these two locations was the pushback from residents who lived in the temporarily closed areas. This could become a major challenge for future School Streets projects in Mississauga.

Kingston

Planning

The School Streets pilot in Kingston had four main objectives; to increase active transportation to and from school, improve safety in and around the school zone, provide opportunities for children to practice independent travel, and to raise awareness on the benefits of active school travel.

The school street was launched at Winston Churchill Public School on a portion of MacDonnell Street, allowing a 200 metre school street zone. It was part of a larger research project, “Levelling the Playing Fields” led by researchers at Queens University and the University of Montreal who were interested in evaluating School Streets and their impacts. The researchers selected schools based on three main criteria:

- The school is not on a major public transit route or arterial road

- There is a high proportion of children within active transportation range

- The principal and school community are supportive

Of the six schools that were approached, Winston Churchill PS was the only school that accepted.

The project researchers collaborated with the Kingston Coalition for Active Transportation (KCAT) to develop the pilot, who then implemented the school street in partnership with the City of Kingston. The planning of the project involved school staff, school parents, local residents, and City staff, who were engaged via virtual meetings, informational letters, door-to-door meetings, and online surveys.

Implementation

This school street ran every morning and afternoon for the entire 2021-2022 school year, making it the longest School Streets program of the five pilots. A portion of MacDonnell Street was closed for 25 minutes every morning (8:40-9:05 am) and for 25 minutes every afternoon (3:20-3:45 pm). To close the street, KCAT implemented lightweight barricades, road closure signs, and placed volunteers at both ends of the closure. The vehicles that were permitted entry (residents and school staff) were required to drive at a walking pace alongside a volunteer.

Programming

There was no programming or activities on this school street, as stakeholders requested the space to be used only for school travel purposes. However, KCAT organized a party for the final week of the program that included music, activities, and visits from city officials.

Results

In October 2021, 65% of children pursued active travel to school (54% walked, 10% biked, 1% rolled), but by February, this figure dropped to 56%, with nobody choosing to bike or roll. This could have been a result of the colder weather during February, making active travel to school more difficult.

School Streets volunteers out on the first snowy day of the school year (photo by: Dr. Patricia Collins via Twitter)

The school street, however, served other benefits, such as providing parents with a space to meet and mingle with other parents. The survey showed that 49% of parents found School Streets helpful in them meeting other parents. The School Streets program had an overall positive response from parents, with 76% in support of future School Streets projects, 44% claiming an improved sense of safety, and 46% stating an increase in their children’s interest in active travel.

Alternatively, residents of the neighbourhood were least supportive of the project, as they felt the school street made it more inconvenient for them to leave or return home.

This pilot program in Kingston was brought to city council in June of 2022, where they approved the expansion of School Streets programs in the city. This means that future School Streets programs only require approval from the Department of Transportation Services, and that Winston Churchill PS was approved to continue the program for the 2022-2023 school year. There is a lot of interest within the City of Kingston to expand School Streets, however, there is currently not enough funding or staff capacity to meet the demand.

Key Findings

The key findings are based on the available data that was collected at pilot sites, either validating previous research or introducing new insights. The 11 key findings across sites include:

- School Streets encourage walking and cycling

- School Streets support community building and social connection

- School Streets raise community awareness on road safety issues

- School Streets do not increase traffic on surrounding streets

- School Streets improve air quality in front of schools during the closure periods

- Each school street is unique to each site

- A plan for project implementation is vital for reassuring critics

- There is no standardized municipal permit process for School Streets

- Municipal participation and support are keys factors for success

- Peer-to-peer support across school street sites aid the planning process

- Communities are eager for more opportunities to use the road as public space

Recommendations

The recommendations section focuses on both recommendations for planning a school street and recommendations for municipalities to support the wide-spread implementation of School Streets.

Recommendations for Planning School Streets

Planning:

- Assemble a team with both municipal and school involvement

- Incorporate the School Streets within existing active school travel programs

- Collaborate with like-minded groups across the country to share learnings to support implementation

Community Engagement:

- Ensure community engagement is meaningful, equitable, accessible, and begins as early in the planning phase as possible

Implementation:

- Animate the school street space

Recommendations for Municipalities

- Simplify the permit process for temporary road closures

- Scale-up to longer-term pilots

- Incorporate School Streets into planning policies and/or strategies

What’s Next?

The OSSP project provided the opportunity to test previous research findings, refine approaches, and develop key recommendations for scaling-up School Streets projects across the country. The next steps for this project include dissemination of research findings (Webinar 1. hosted by 8 80 Cities and GCC on November 16, 2022, and webinar 2. hosted by APBP on December 14, 2022) and pursuing future opportunities to implement more School Streets.

If you’re looking to bring a school street to a school near you and think we could help, please get in touch!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks